.

Originally Published: “I Had To Kill,” by George Beltz, Front Page Detective, May, 1950.

Editor’s Note: Articles written for detective magazines during the 1940s, 50s and 60s often incorporated “recreated dialogue” in order to both tell the story and to advance the storyline. For readers today, this dialogue will feel contrived and trite. In spite of this, these writers made every effort to present a factual story. In nearly all cases, they were newspaper reporters with close knowledge of the case who wrote for crime magazines to earn extra money. Most of them wrote under a pseudonym, but not all.

Want to Read this Story Later on Your Tablet?

Download PDF File of “The Marian Baker Murder of 1950″

Lancaster, Pennsylvania, January, 1950

What is in a murderer’s mind when his fingers close around the windpipe of his victim and the pressure is increased until he feels the crunching of cartilage? Does he look down at what he has done, and then, like a child with a broken toy, try to set the sagging head straight-again? Does he brush back the wisps of hair that have fallen out of place, and, as he feels the skin grow first cool, then cold, is there a feeling of panic and revulsion?

Somewhere in Lancaster, Pa., the night of January 10, 1950, a man knew the answers to these questions, and, buried under a sheet of corrugated roofing, in an abandoned summer bungalow, was a dead girl who had for one fleeting second before she died seen the look in a killer’s eyes that told the story.

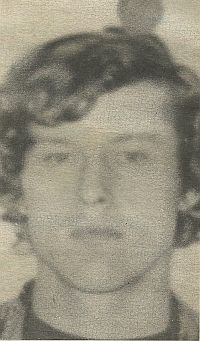

But Marian Baker, 21 years old, engaged to be married, was dead and the dead don’t talk.

Nothing was left of a girl who had pounded a typewriter in the office of Franklin and Marshall College, listened to a softly playing car radio; parked on a lonely hill; learned to cook and to sew so that when she married in June she would make a good housewife. Nothing was left of a girl who looked for an apartment, clipped recipes from women’s magazines, fed a horse a lump of sugar or kissed her fiancé out in front of everybody Christmas Eve when she announced her engagement.

Back in her room was a narrow shelf with a few hats and hanging on a rack, a few dresses; a few trinkets, half a shelf of books, a photograph of a boy, a car and a girl; some letters and a hairbrush. That was all that was left to say there had ever been a Marian Baker.

In another room, a boy sat smoking, looking out of the window. Closing his eyes he felt the throat under his hands. Then he threw the cigarette down, stamped it out, and walked through the door. There was no turning back now. Marian Baker was dead and in all Lancaster only her murderer knew it.

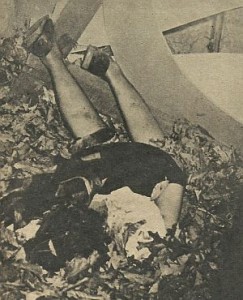

But four days later the whole town knew; the whole state, the whole nation knew. Marian Baker’s body was found under a wooden saw horse, covered by a piece of rusty, corrugated roofing, beneath the porch of a summer cottage on Mill Creek; a cottage the owners visited almost by accident; a discovery made only because two peculiar marks, like those of dragged heels, roused the curiosity of Mrs. Francis Harnish.

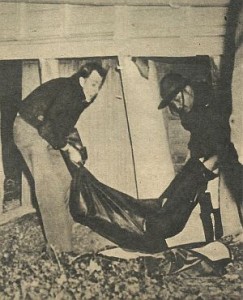

In the failing light of day the yard was roped off and the girl’s broken body was removed from its makeshift grave for Dr. Charles Stahr to make his preliminary examination. State, county and city police made casts of the footprints found in half frozen mud and studied the crooked path left by the killer as he pulled the victim under the house.

Like a wind-fanned flame, word spread over the campus that Marian Baker, whose disappearance four days before had become the main topic of talk, was found; that she was dead and that her killer was not known.

The report had snaked its way across town without missing an ear by the time the sad procession that followed the ambulance was back in town.

“We have to crack this and crack it fast,” Commissioner Fred McCartney said. “This case is front page throughout the East. Up until now it was a missing person we wanted—today it’s a killer. Where are the records on the girl’s disappearance?”

The file on the week long search for Marian Baker was voluminous, but unrevealing. At the time the body was found, a 13-state alarm was in effect and state police, city and county officers were making every effort to locate the missing girl.

Marian had left the college shortly after 1 P.M. on Tuesday, January 10. She went first to the Farmer’s Bank & Trust Company and deposited canteen funds in the amount of $75.

“We traced her from the bank to the post office,” Lancaster Police Captain John Kirchner said. “She mailed a registered letter, then picked up her engagement ring which had been left at a jewelry store for repairs. At 2:15 George Crudden, a newspaperman, saw her downtown. Judging by the time her wrist watch stopped, she was killed exactly 20 minutes later. But that’s as much as we know.”

Marian had been reared by an aunt and uncle who lived a few miles from Lancaster. After getting a job at the college she boarded with friends.

“Nothing there for a clue,” Captain Kirchner said. “She had a 5:30 appointment at a beauty parlor on Tuesday—which was never kept. Fellow workers closed her desk when she failed to come back from her noon errand at the bank.”

“No motive and no suspects,” McCartney said. “What about her fiancé? We have to start some place.”

“I Can’t Believe It!”

Edgar R. Rankin, the 21-year-old youth to whom Marian Baker was engaged, had already spent four sleepless nights aiding in the search for his sweetheart. News of her death had nearly shaken him loose from his reasoning.

“I just can’t believe it,” he said. “I just can’t believe it.” But the lifeless body with the crushed skull that lay on the morgue slab was not to be refuted.

Rankin repeated his original story that he had not seen his fiancée since the previous Sunday when he left her at her rooming house following a date.

“There’s a lover’s lane near the cottage where the body was found,” Sergeant John Auman pointed out. “Do you think she might have gone there with someone else? A college student, maybe?”

“NO SIR!” Rankin’s temper flared at the suggestion. “Marian wasn’t dating anyone but me.”

Rankin was sure of this, but the troopers weren’t. The girl had vanished from the crowded streets of a comparatively large city. No one could have forced her into an automobile without attracting attention.

“My guess is she went out with someone else,” one of the troopers said after Rankin left. “A last date with some suitor after she announced her engagement. But the guy was jealous and refused to call it quits. It’s happened before and it will happen again.”

Following this theory, a visit was paid to the Weaver home where Marian had resided. The girl had been considered a guest rather than a boarder. She and Mrs. Weaver went to grade school together and werelifelong friends.

“Then you should know something of her social life,” Aumon said.

“Marian and Edgar went together for nearly two years,” Mrs. Weaver said. “In all that time she dated another boy on only one occasion. That was about a year ago when she and Edgar had a quarrel. It was just a silly little spat and they made up quickly.”

“You’re sure Rankin didn’t brood about it?”

“I should say not. He forgot the, whole thing. Since then the two of them have spent all their time apartment hunting and Marian has been learning to cook and sew.”

Sergeant Aumon was shrewd enough to see the line of questioning was leading nowhere. Marian probably accepted a lift in the car of a person she thought was a friend, but she certainly hadn’t gone off on an afternoon date with someone other than her boyfriend.

“Marian fully intended to return to the college or she would have locked up her desk for the day,” Aumon theorized. “But on the way back she met someone—a student, a professor, or just an acquaintance who happened to be going her way. Whoever it was, he took the girl out to Mill Creek and killed her. Our job is to find that man!”

It was easy to say, hard to do. F. & M. was a coeducational school with several thousand students on its roster. In addition, the slain girl had many friends and acquaintances off the campus.

On Sunday, Dr. Stahr definitely set the time of death as Tuesday afternoon, January 10. His post-mortem report stated that the victim had been strangled and beaten to death but she had not been sexually assaulted. Intent to do so, however, still remained as a possible motive for the crime.

“We’re slicing things pretty thin,” Aumon said thoughtfully, when he heard this. “If Marian Baker’s watch was correct, she was picked up, driven three miles into the country and murdered—all in the space of 20 minutes after George Cudden saw her on a downtown street. Her watch was broken at 2:35.”

Who Drove The Coupe?

Captain Kirchner and Commissioner McCartney enlisted the aid of college president Theodore Distler in the herculean task of identifying every F. & M. student who had been absent from class on the afternoon of the slaying. A probe of all known sex offenders also got underway.

“We know this girl was dragged to the cottage,” Aumon told the troopers. “That means she was slain elsewhere perhaps in a car. I want all garage and car cleaning establishments posted. Watch for bloodstains on the upholstery or floor of every car that comes in.”

Identification men were also doing a job with the killer’s footprints found in the mud at the Harnish cottage. The moulages (plaster casting) were too rough for identification, but temperature readings for the murder date were obtained and experts accurately estimated the consistency of the half frozen soil. By measuring the size and depth of the’ footprints they were able to state with a fair degree of accuracy that the murderer was tall, heavily built and probably a young and active man.

Meanwhile, outraged citizens, anxious to lend every support to the killer hunt, were pouring tips into headquarters: The first definite lead came from a neighbor who lived several doors beyond the Weaver home.

“This may not help much,” she said. “But on Tuesday, about 5 o’clock, my 8-year-old daughter told me she saw Marian come out of the house carrying a suitcase. She said she got into a car with a man who wasn’t Ed.”

“Could she describe the car at all?”

“Only that it was a coupe.”

Aumon questioned the youngster at length but his slowly rising hopes plunged like a lead weight in water as he discussed this latest development with Sergeants James Haggerty and V. E. Simpson.

“She must be mistaken,” Haggerty argued. “Unless the killer was shrewd enough to reset his victim’s wristwatch and then deliberately break it, Marian Baker had been dead for several hours when this child thought she saw her.”

“And don’t overlook the medical report,” Simpson remarked. “Analysis of her stomach contents indicate the victim died within three hours after eating her last meal at noon.”

“We can’t get around that,” Aumon admitted. “But I do have a hunch about the watch.”

A phone call to Mrs. Weaver established that Marian customarily wound her wrist watch at approximately 7 A.M. before leaving for work. Aumon then phoned officials or the Hamilton Watch Company in Lancaster.

“Would it be possible,” he asked, “to check the spring tension of a watch and find out how long it has run since last being wound?”

Assured that such a procedure was entirely feasible, the sergeant sent in the broken watch for testing. If it had run seven and a half hours, the time of death would be confirmed. If longer, then the killer was cagier than was thought.

By Monday morning none of the lines out had brought in a nibble. Edgar Rankin described his fiancée’s missing engagement ring as a small diamond in a gold setting with baguettes on either side. This information was passed on to pawnbrokers in Lancaster and nearby towns on the off chance that the killer would attempt to cash it in.

Friends and acquaintances of the victim were brought in for questioning and then released. Anyone without an alibi for the time of death was under suspicion and suspects were a dime a dozen. Captain Kirchner and President Distler swelled this number when they reported 175 students were absent from their classrooms on the previous Tuesday.

“Talk to those who had girl trouble first,” Aumon ordered. ‘We’ll get to the rest later, if necessary.”

The absentee students were processed quickly, but out of the welter of statements, one fact stood out from all others. Marian Baker had eyes only for Ed Rankin. Donald Mylin, treasurer of the college, recalled that she had gone out with a pre-med student who was graduated in June, but it was nothing serious. Many students frankly admitted an interest in the pretty girl, but all declared their advances had been firmly declined.

A phone call from the Hamilton Watch Company verified the time element. The watch still had 35 hours running time left which meant, if it was wound at 7 A.M., it was broken at 2:35 P.M.

But Aumon was far from satisfied with the progress the case was making. “Here’s a girl who doesn’t date,” he said. “Engaged to be married, learning to cook everything. So she’s given a ride by someone she knows. But why did she go out to Mill Creek? That’s an off-trail spot where only young lovers go.”

“I think I’ve got the answer to that,” Captain Kirchner said. “I’ve been given a tip that might be worth looking into. Marian Baker was learning to drive a car. She’d been taking lessons secretly, planning to surprise her friends.”

“Of course, of course!” Aumon was amazed by the simplicity of the solution. “A back road, away from traffic, where she could practice. Nothing better than Mill Creek for that. Who was the instructor?”

“I wish I knew,” Kirchner said. “Someone not connected with the college, I understand, but no one can give me his name. If only the girl hadn’t been so secretive . .”

“We’ll find him,” Aumon said confidently “Someone knew about those driving lessons or you couldn’t have been tipped off. It’s simply a matter of time.”

The questioning of absentee students was abandoned as investigators concentrated on finding the man who had been teaching Marian Baker to drive.

In the midst of this flurry of activity a man who introduced himself, as a local mortician requested an interview with Aumon.

Question Alerts Mortician

“It’s about a student,” the undertaker said nervously. “The boy asked me how long it takes a body to decompose. I didn’t think much about it at the time, but since this murder, well, I thought I’d better get in touch with you.”

“Good Lord!” Aumon said. “Who was he?”

“His name is Alvin Edwards.”

Captain Kirchner went through the student list to learn whether Edwards was in the clear. “No dice,” he said, after a moment. “Edwards has an air tight alibi. On the afternoon of the murder he went to a movie with some friends.”

“Morbid curiosity, I suppose,” Aumon agreed. “What else have we got?”

“Not much,” the captain admitted. “Right now we’re looking for Jim Withers, the chap who dated Marian last June. Someone saw him in town a week ago and I thought he might have looked her up again.”

“Might as well forget Withers,” Aumon said. “The man I want is the fellow who was teaching Marian Baker to . . .”

He was interrupted by a sergeant who hustled a total stranger into the office. “Here’s someone you’ll want to see, John,” the sergeant said.

Aumon studied the tall, thin man who twisted his hat nervously and looked at him with an uncertain smile. “I’m Ben Williams,” he said quickly. “Drive a bread truck here in town.”

“Sit down, Ben. What’s on your mind?”

“Well, I . . you see, I knew Marian Baker pretty well. In fact, I’m the one who was teaching Marian Baker to drive.”

The sergeant kept his face blank.

“I intended to keep out of this.” Williams said. “Then I heard you were looking for the man Marian was taking lessons from. So I thought I’d better let you know I didn’t do it.”

“Right now you’re an A-I suspect,” Aumon said gravely. “If you are innocent, I hope for your sake you have an alibi.”

“I think I have,” he said. “Last Tuesday delivered bread all day.”

“Marian Baker was picked up, driven to Mill Creek and murdered all within 20 minutes,” the sergeant pointed out. “Your alibi isn’t tight, mister! Suppose you were driving around in a bread truck. There was nothing to keep you from taking this girl out to Mill Creek.”

“I covered a rural route that day,” Williams explained. “At the time of the murder I was at least 15 miles from town in the northern part of the county. What’s more, I can take you to every stop I made.”

Aumon felt his best lead slowly collapsing from under him. “We’ll give you a chance to prove that,” he said, but mentally he crossed Ben Williams from his list. The man’s alibi was too good to be faked, and in a matter of time the driver was given back his freedom, and cleared unconditionally of any complicity in the slaying.

“That leaves us with Jim Withers,” Aumon said bleakly. “Perhaps Kirchner isn’t so far wrong as I thought.”

That evening, Major William Hoffman, commander of the Philadelphia state police barracks, arrived in Lancaster to assist with the investigation. Hoffman had been watching the case closely and was much concerned over the last lead that had blown up in their faces.

“We simply must get results,” the major insisted. “Everything indicates a local man—someone known to the victim. Find him!”

“Jim Withers seems to be our best bet,” Aumon assured him. “We’re cooperating with Captain Kirchner and his men. So far we’ve learned that Withers left Philadelphia, heading west. He stopped in Lancaster to visit friends and was here until last Tuesday evening. He left then, intending to drive at night and avoid traffic. But no one seems to know his destination.”

“Did you get the make and license number of ‘his car?”

“Not the license,” Aumon admitted. “We have a description on the teletype now, and the number will go out as soon as the license bureau opens in the morning.”

“What about students?”

“All but 20 checked out okay. The remainder are being questioned.”

No one wanted to admit it, but the Withers’ lead was actually a forlorn hope. True, he had dated the girl six months previously, prior to his graduation. But there was no record of his ever having tried to get in touch with her again—and no reason for him to have returned to town with murder in his heart.

“We’re going to find him,” Aumon predicted. “But he’ll have an alibi. What then?”

The pawn shop alert had netted nothing; no one had attempted to dispose of the diamond engagement ring. Nor did any bloodstained cars show up in local garages. And one by one the 20 students were being alibied and released.

On Wednesday morning, Corporal James Kane sought out Alvin Edwards, the student who had asked about decomposing bodies. Sensing that the murder of Marian Baker was fast heading into the limbo of unsolved crimes, Kane was determined to crack it.

“Not My Idea”

“I’m curious about that remark son,” he said mildly. “Why did you ask how long it takes a body to decompose?”

Edwards, a clean cut youth and excellent student, smiled sheepishly. “Actually, it wasn’t my idea,” he admitted. “One of the seniors asked me and I was curious enough to try to find out.”

Corporal Kane almost swallowed his tongue. Here, it seemed, might be one of those almost unbelievable breaks of which every investigator dreams but rarely encounters. “What,” he asked, “is this senior’s name?”

“Gibbs,” the boy told him. “Edward L. Gibbs. He and his wife live at the college dormitory. I believe she works for the Armstrong Cork Company.”

Sergeant Aumon was alone when Kane entered his office. He pointed to a teletype message lying on the desk. “There it is, Jim Withers was picked up in Pittsburgh. Says he spent Tuesday afternoon with a Lancaster girl. The boys went to see her a few minutes ago. When she backs up his story . . . well, we’re washed up.”

Kane smiled briefly. “Not quite,” he said. “Listen to this . . .

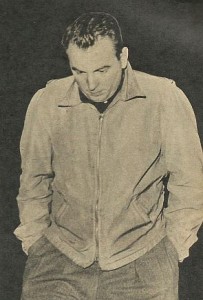

His report was like a shot of adrenalin to the weary Aumon. Gibbs was among the students already questioned. Attention was centered on him early in the investigation because of a long scratch on one cheek. But he was dismissed when a fellow student admitted having inflicted it during basketball practice. Gibbs, however, had not yet cleared himself completely and was scheduled for a complete cross-examination in the morning.

College records identified him as a 25-year-old veteran who served with the Army Air Force in Europe; an excellent student, supposedly happily married. But he did know Marian Baker, and on several occasions had driven her to the bank when she placed canteen funds on deposit.

“Gibbs could be our man,” Kane declared.

But Edward Gibbs was not to be found in any of his usual haunts—and for a very good reason. At that moment he had walked into President Distler’s office and demanded an audience. Distler, in conference with Max Hannum, publicity director of the college, looked up in amazement when the disheveled youth brushed by the secretary who sought to restrain him and forced his way.

“Sure, Ed, we know you,” Hannum assured him. “Come in and sit down.”

Gibbs shook his head. “You don’t know me. You only think you do.”

It was the kind of statement the men ordinarily would have ignored, but these were not ordinary times for the harassed college officials. Simultaneously the same thought flashed into the minds of the two men. “This is it, yet it can’t be. Things like this just don’t happen.”

“I Did It”

But all doubt was dispelled when Gibbs, haggard and wild eyed, said, “I’m your man. I did it.”

Stalling for time, Distler countered with a question. “What did you do, Ed?”

“Killed Marian.”

Two Baltimore reporters entered the outer office just then, wanting an interview. But Distler and Hannum were holding a stick of dynamite with the fuse lit. They dared not let the press in on what was transpiring until definite proof of guilt had been established. The truth was, both men were hoping against hope that the student’s confession was untrue, perhaps brought on by nervous tension and overwork.

But the reporters were suspicious. They lingered for ten minutes while Gibbs sobbed in a corner and Distler and Hannum engaged in a loud discussion on irrelevant subjects trying to throw the reporters off. Eventually the newsmen departed in disgust.

With one hand on the telephone, Dr. Distler said. “Are you sure, Ed, that this is not hysteria or hallucinations?”

“It’s hard for me to believe, too,” the youth answered. “But I can describe the whole thing, show you where I hid some of the stuff.”

Convinced at last, President Distler lifted the phone . . .

Edward Gibbs made a full confession to the brutal crime. “It wasn’t a date,” he insisted, after explaining how he met Marian Baker on a downtown street and offered to drive her back to the college. “We just went the long way around.”

At the Harnish cottage, Gibbs had a sudden impulse to choke his lovely companion. But she fought free and fled from the car.

“I followed her,” the student murmured in an almost inaudible voice. “When I caught her I choked her again and again. But when I saw her lying so still I knew if she wasn’t dead, then I had to kill her. So I went back to the car and got a lug wrench out of the trunk. I hit her with that until I was sure she was dead. I—I guess I was out of my mind.”

Returned With Shovel

Suddenly overcome by the enormity of his crime, Gibbs fled the scene. But he returned within an hour, bringing a shovel to dig a grave. The frozen ground prevented this and after removing his victim’s ring and taking her purse, he dragged the body under the cottage and covered it with the sheets of metal roofing.

“I was sure nobody would be able to find it for a long, long time,” he went on. “I had an idea that when spring came and the ground softened up a little, I might come back and bury her. I didn’t figure anyone would come around the cottage in the winter.”

“What did you do with her purse?” Aumon asked.

“I threw it away. There was $14 in it. I took the money and spent it.”

“And the ring?”

“That I flushed down a filling station toilet.”

The ring was recovered from the drain trap. Other officers, searching Gibbs’ dormitory home, found a jacket stained with the blood of his victim. At the same time, an electric magnet located the lug wrench in Conestoga Creek where it had been thrown by the killer.

Proof of guilt was now established, but officers scoffed at the “impulse” motive for the crime. In their opinion, Marian Baker was slain when she resisted the sexual advances of her supposed friend.

After reenacting the slaying on two different occasions, Gibbs was given a hearing in the office of Alderman J. Edward Wetzel on January 19. He listened in silence as District Attorney John M. Ranck read a warrant which charged him with “wilfully, feloniously, maliciously and premeditatively” choking the pretty secretary to death.

With no change of expression, Gibbs then heard himself ordered held without benefit of bail for trial in the Lancaster County court on March 13. At that time the final curtain will be rung down on the campus drama of life and passion and sudden death.

End of Story.

Conclusion to Story:

At his trial, Edward L. Gibbs was found guilty of first degree murder and he was executed on April 23, 1951.

Follow Us On Facebook

—###—